$$ \sim * \backsim $$

Table of Contents

$$ \backsim * \sim $$

§ 15. Nonlocal Games

The CHSH game falls within the class of nonlocal games.

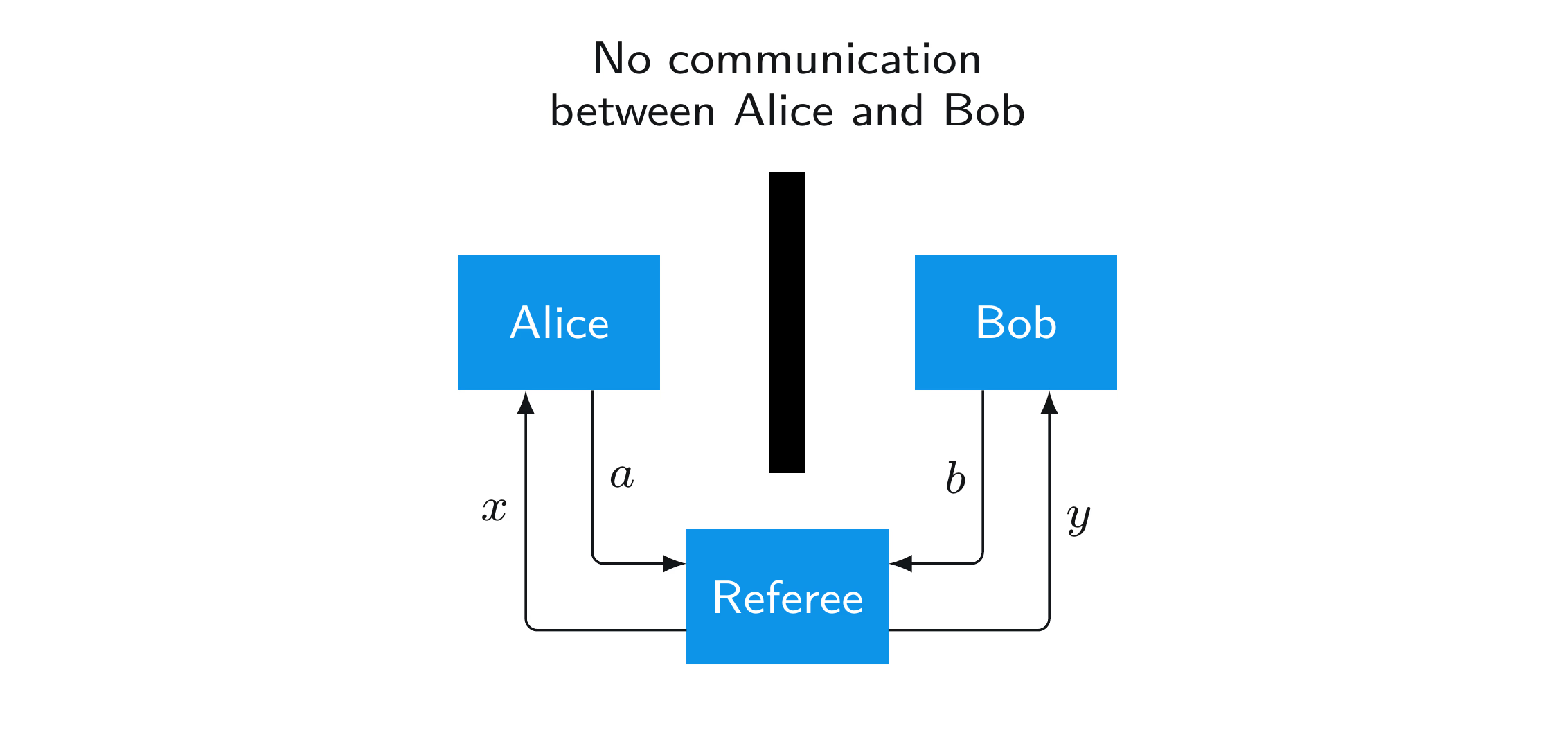

The game is a cooperative game where Alice and Bob work together to achieve an outcome. There also exists a referee who ensures Alice and Bob abide by a strict set of guidelines.

Nonlocality implies Alice and Bob are outside of each other’s light cones. That is, it is impossible to communicate.

The referee first asks Alice and Bob a question. The letter $x$ refers to Alice’s question and the letter $y$ refers to Bob’s question. In the CHSH game we think of $x$ and $y$ as being classical bits.

The referee uses randomness to select these questions. There is some probability $p(x, y)$ associated with each possible pair $(x, y)$ of questions. Everyone in the game knows these probabilities, but no one knows exactly which pair ($x, y$) will be chosen until the game begins and they can’t communicate.

When the game begins, Alice and Bob receive their questions. They provide answeres $a$ and $b$, respectively. Again, these are classical bits in the CHSH game.

At this point the referee decides whether Alice and Bob win or lose depending on whether or not the pair of answers ($a, b$) is deemed correct for the pair of questions $(x, y)$ according to the rules. Different rules mean different games; the rules for the CHSH game will be described below.

The following diagram illustrates the interactions in nonlocal games.

Again, Alice and Bob do not know which questions will be asked, and what each other’s responses are. This is what makes the nonlocal game a game.

§ 16. The CHSH Game

The letters CHSH refer to the authors – John Clauser, Michael Horne, Abner Shimony, and Richard Holt who presented the idea in their 1969 paper. (I actually had the pleasure of attending a lecture by John Clauser – interesting guy.)

Here is the rigid description of the CHSH game. Again, $x$ is Alice’s question, $y$ is Bob’s question, $a$ is Alice’s answer, and $b$ is Bob’s answer:

- $x, y, a, b \in$ {0, 1} are all classical bits.

- The referee chooses the questions $(x, y)$ at random. Each of the four possibilities (0,0), (0,1), (1,0), (1,1) are selected uniformly with probability $\frac{1}{4}$.

- The answers $(a, b)$ win for the questions $(x, y)$ if and only if $a \oplus b = x \wedge y$.

In logic the $\wedge$ operator is the same as and in python. That is, $x \wedge y$ is the same as x and y. If either $x$ or $y$ is 0, $x \wedge y$ is false / 0.

The $\oplus$ operator represents the exclusive-or (XOR) operation which returns True if $x$ and $y$ are different, and False if they are the same.

| (x, y) | win | lose |

|---|---|---|

| (0, 0) | a = b | a ≠ b |

| (0, 1) | a = b | a ≠ b |

| (1, 0) | a = b | a ≠ b |

| (1, 1) | a ≠ b | a = b |

Check to make sure you understand everything so far.

Limitations of Classical Strategies

Let’s consider the classical strategies for Alice and Bob in the CHSH game.

Deterministic Strategies

Deterministic strategies are the most intuitive. Alice’s answer $a$ is a function $a(x)$ of the question $x$ she recieves, and likewise for Bob.

No deterministic strategy can win the CHSH game every time. You could brute force show this by going one-by-one through all possible functions $a(x)$ and $b(y)$ that give Alice and Bob their answer for each pair $(x, y)$.

We can also derive this fact analytically:

-

If Alice and Bob’s strategy wins for $(x, y) = (0, 0)$, then $a(0)$ must equal $b(0)$

-

If Alice and Bob’s strategy wins for $(x, y) = (0, 1)$, then $a(0)$ must equal $b(1)$

-

If Alice and Bob’s strategy wins for $(x, y) = (1, 0)$, then $a(1)$ must equal $b(0)$

If their strategy wins for all three cases, we have

$$ b(1) = b(0) = a(1) = a(0) $$

Which would make Alice and Bob lose in the final case $(x, y) = (1, 1)$ which requires that $a(1) \neq b(1)$. Therefore, the maximum probability for Alice and Bob to win a given $(x, y)$ is 3/4.

Probabilisic Strategies

Perhaps including the possibility of Alice’s and Bob’s answers having a shared randomness, correlation could help? No.

Every probabilistic strategy is essentially just a random mix of deterministic strategies.

Since a random mix cannot surpass the maximum success probability of a deterministic strategy, we conclude that any classical strategy has a maximum probability of 3/4 for Alice and Bob to win.

CHSH Game Strategy

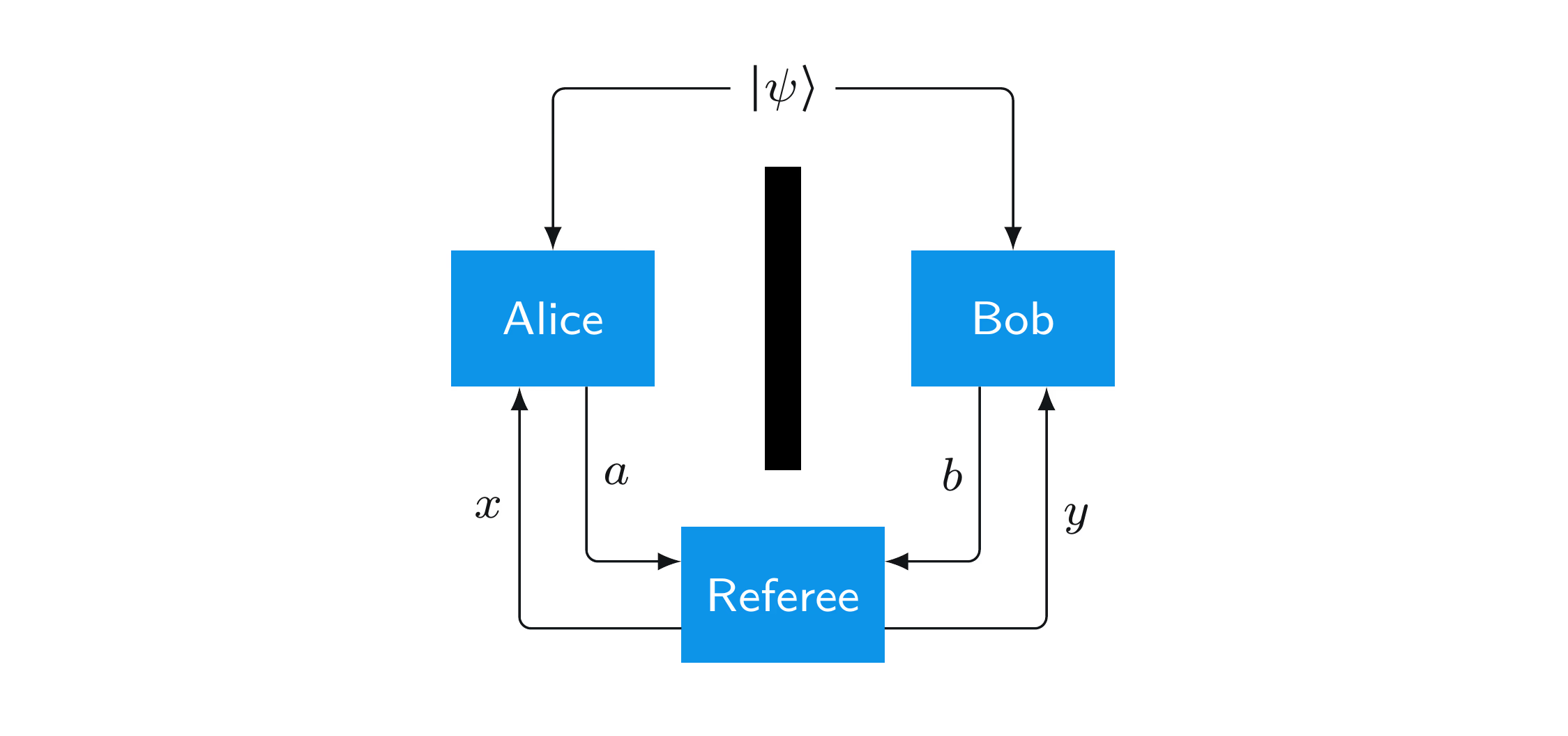

What if Alice and Bob shared an entangled quantum state which they prepared prior to the game? Could that improve their chances above 3/4?

Yes. Let’s see how entanglement helps.

Required knowledge

Statevector Definition

Let’s define an arbitrary qubit statevector $|\psi_\theta\rangle, for each real number $\theta$.

$$ |\psi_\theta\rangle = \cos\theta |0\rangle + \sin\theta |1\rangle $$. Therefore, some simple examples:

$$ \begin{align} |\psi_0\rangle &= |0\rangle \\ |\psi_{\pi / 2} &= |1\rangle \\ |\psi_{\pi / 4} &= |+\rangle \\ |\psi_{-\pi / 4} &= |-\rangle \end{align} $$

Inner Product

Looking at the general formula for $|\psi_\theta\rangle$, we see the inner product between any two of these statevectors has the formula:

$$ \langle \psi_\alpha | \psi_\beta \rangle = \cos\alpha \cos \beta + \sin\alpha \sin\beta = \cos (\alpha - \beta) $$

This result follows from the trigonometric angle addition formula. Thus, the inner product is equal to the cosine of the angle between the two state vectors.

Now let’s compute the inner product of the tensor product of any two of these vectors with the $|\phi^+\rangle$ state:

$$ \langle \psi_\alpha \otimes \psi_\beta| \phi^+\rangle = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}(\cos\alpha \cos \beta + \sin\alpha \sin\beta) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\cos(\alpha - \beta) $$

We get a similar expression, just with a factor of $\sqrt{2}$ in the denominator. The significance of this inner product will become clear shortly.

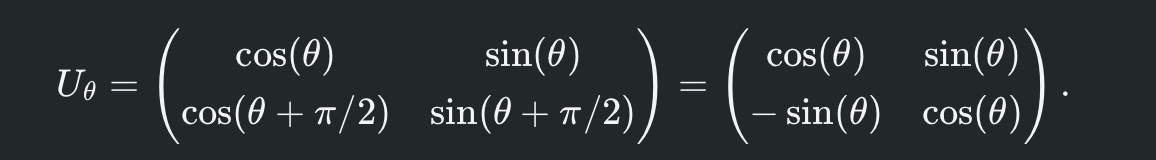

Unitary Matrix

Next, let’s define a unitary matrix $U_\theta$ for each angle $\theta$ as follows:

$$ U_\theta = |0\rangle \langle \psi_\theta | + |1\rangle \langle \psi_{\theta + \pi/2} | $$

This operation essentially maps $|\psi_\theta\rangle to $|0\rangle$ and $|\psi_{\theta + \pi/2}\rangle$ to $|1\rangle$. Taking the inner product of $U_\theta$, we find that

$$ \begin{align} U_\theta U_\theta^\dagger &= (|0\rangle\langle \psi_\theta| + |1\rangle \langle \psi_{\theta + \pi/2} |)(|\psi_\theta\rangle\langle 0 | + |\psi_{\theta + \pi/2}\rangle\langle 1|)\\ &= |0\rangle\langle \psi_\theta | \psi_\theta \rangle \langle 0 | + |0\rangle\langle \psi_\theta | \psi_{\theta + \pi/2}\rangle \langle 1 | + |1\rangle \langle \psi_{\theta + \pi/2} | \psi_\theta \rangle \langle 0 | + |1\rangle \langle \psi_{\theta + \pi/2} | \psi_{\theta + \pi/2} \rangle \langle 1 \rangle \\ &= |0\rangle\langle 0 | + |1\rangle \langle 1| \\ &= \mathbb{1} \end{align} $$

The matrix representation of $U_\theta$:

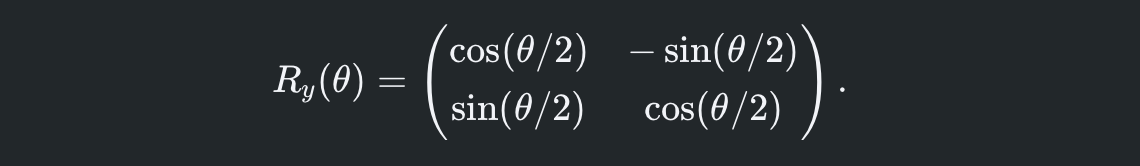

Which is a rotation matrix that rotates 2d vectors by an angle of $-\theta$ about the origin. Using the standard convention for defining rotations, we have $U_\theta = R_y(-2\theta)$, where

Is a rotation matrix about the $y$-axis.

Strategy description

Now we can describe the quantum strategy.

- Alice and Bob start the game sharing and e-bit. Alice holds qubit $A$, Bob holds qubit $B$, and together the two qubits $(A, B)$ are in the $|\psi^+\rangle$ state.

Alice’s Operations

$$—\sim*\backsim—$$

Alice’s actions are as follows:

- If her question is $x = 0$, she applies $U_0$ to her qubit $A$.

- If her question is $x = 1$, she applies $U_{\pi/4}$ to her qubit $A$.

$$ \begin{cases} U_0 &\qquad x = 0 \\ U_{\pi/4} &\qquad x = 1 \end{cases} $$

After she applies this operation, she measures $A$ with a standard basis measurement and sets her answer $a$ to be the measurement outcome.

Bob’s Operations

$$—\sim*\backsim—$$

Bob’s actions are as follows:

- If his question is $y = 0$, he applies $U_{\pi/8}$ to his qubit $B$.

- If his question is $y = 1$, he applies $U_{-\pi/8}$ to his qubit $B$.

$$ \begin{cases} U_{\pi/8} &\qquad y = 0 \\ U_{-\pi/8} &\qquad y = 1 \end{cases} $$

After he applies this operation, he measures $B$ with a standard basis measurement and sets his answer $b$ to the measurement outcome.

$$—\sim*\backsim—$$

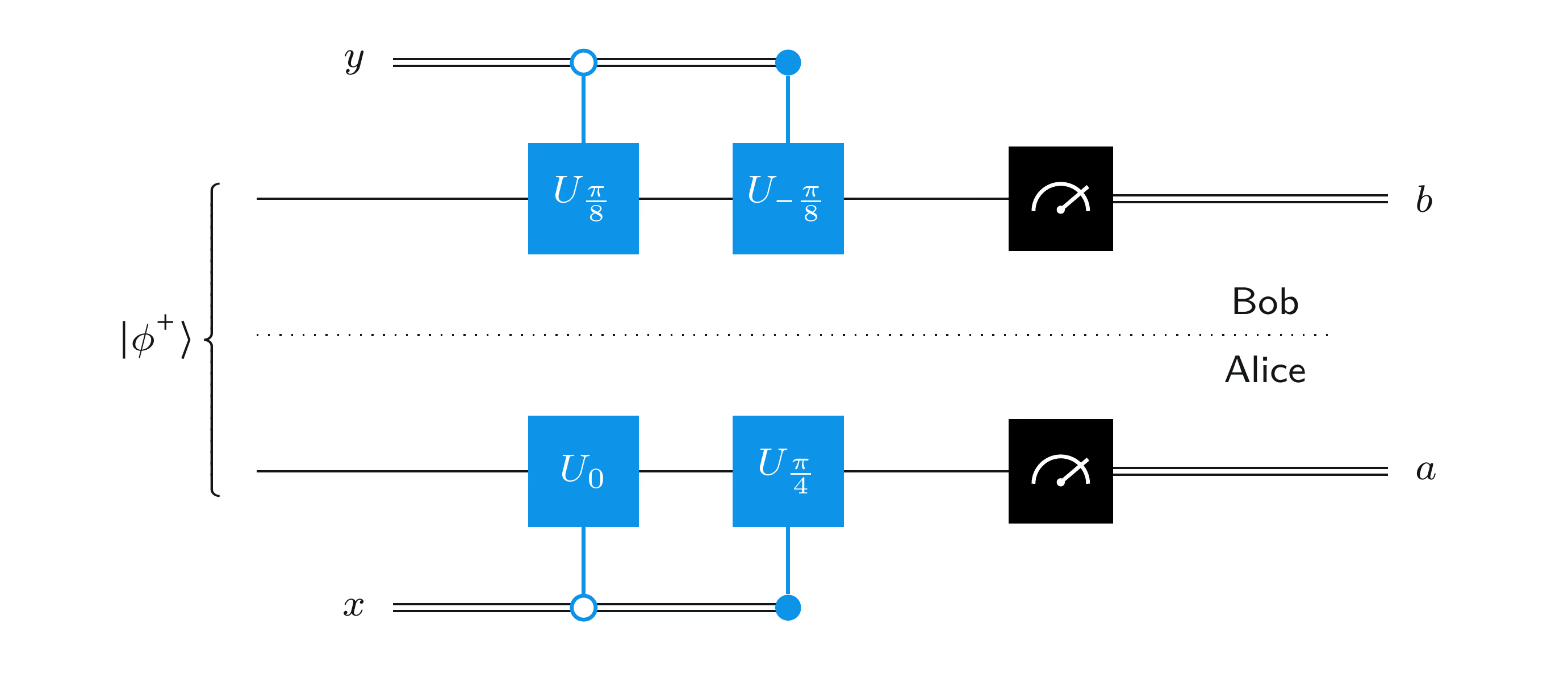

Here is the quantum circuit diagram illustrating the strategy:

In the diagram, we see two ordinary controlled gates where the control is represented by a filled-in circle. Additionally, there are two other controlled gates with an open circle. The open circle indicates a different type of control gate: one where the gate is performed when the control qubit is in the $|0\rangle$ state, the inverse of an ordinary controlled gate.

Now let’s go through the analysis case-by-case.

Analysis

- Case 1: $(x, y) = (0, 0)$.